I was in two minds about whether to bother writing up my annual review of the books I most enjoyed this year. Then I saw a LinkedIn post from my erstwhile colleague Majd Yafi saying how much he enjoys these end‑of‑year reading round‑ups, and my wife added that they make me seem “more human”. That felt like reason enough, particularly in a year marked by an ever‑increasing tide of AI‑generated prose.

Fiction

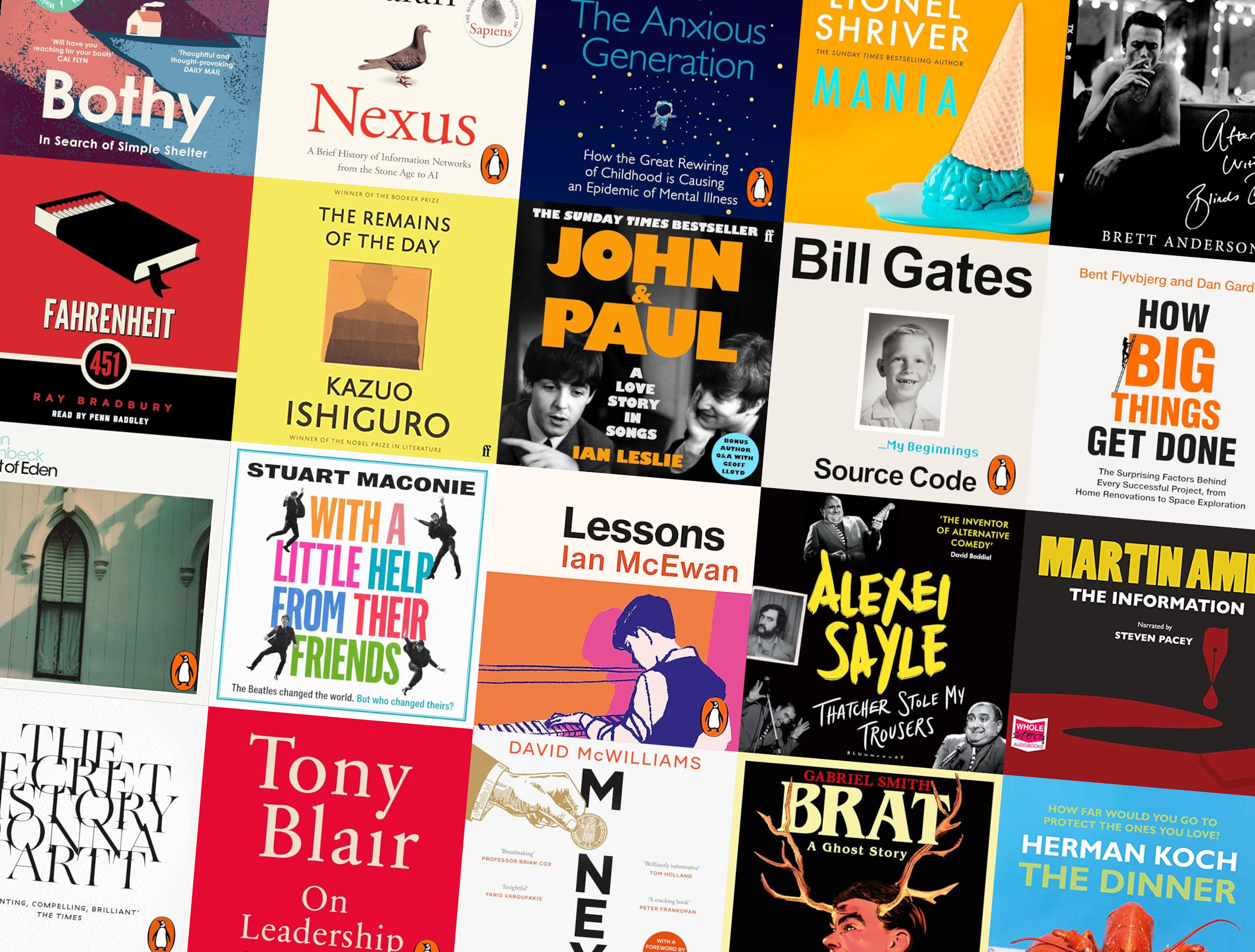

Somewhat to my own surprise, my favourite read of 2025 was John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel East of Eden. Surprising because I didn’t actively seek it out. My wife was clearing an overstuffed bookcase and asked whether I wanted to read it before it was donated, and I absent‑mindedly said yes. In most years I read far more non‑fiction than fiction, but 2025 saw a noticeable shift. It has not been the easiest of years, with family health issues and an unexpected stretch of time between contracts, and I found myself retreating into novels more than usual.

Steinbeck’s evocation of the Salinas Valley in early twentieth‑century California is luxuriant without being indulgent, and the interwoven lives of the Hamilton and Trask families feel satisfyingly large and messy. I was particularly taken with Lee, whose quiet wisdom and moral clarity anchor the novel, and with Kate, one of literature’s great unapologetic villains. I dimly recall being forced to read Steinbeck for GCSE English – The Pearl, I think it was – and bouncing off it at the time. By contrast, East of Eden was a gloriously meaty feast of a novel, one I actively looked forward to returning to each evening. It has nudged several other “big books” further up my to‑read list for 2026.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt is one of my daughter’s most‑loved and most‑revisited books, so curiosity eventually got the better of me. It is a quintessential “dark academia” novel, following a small, insular group of students at an elite American college. Like East of Eden, it is generously long and largely linear, and I enjoyed spending time with its sharply drawn, frequently infuriating characters. Knowing the destination from the outset does nothing to dull the tension along the way. I will confess to a pang of disappointment at Camilla’s inevitable rejection of Richard’s marriage proposal — after so much cultivated misery, I found myself wanting, perhaps naively, a scrap of happy ever after at the end.

I have enjoyed many of Ian McEwan’s novels over the years, but it took me a couple of attempts to properly get into Lessons, his seventeenth. When I first bought it, I suspect I simply wasn’t in the mood for a long work of fiction. That resistance evaporated in 2025. Spanning roughly seventy years of its protagonist’s life, the novel moves through the Cuban Missile Crisis, Chernobyl, Brexit and COVID, using personal drift and accident as a counterpoint to historical upheaval. I was quietly sorry to finish it. I am intrigued by the premise of McEwan’s forthcoming novel, What We Can Know, set in 2119, which I plan to read next year.

During the summer I travelled with my sons through the Netherlands, Germany and Czechia. I had the bright idea of reading a notable novel by an author from each country, selected from the culture sections of the relevant Lonely Planet guidebooks. This was only a partial success. I abandoned Alone in Berlin by Hans Fallada – relentlessly bleak, though very much by design – and The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, whose prose style I simply couldn’t settle into. I did, however, finish and enjoy my Dutch selection, The Dinner by Herman Koch. Structured around the courses of a single meal and intercut with revealing flashbacks, it is brisk, unsettling and darkly funny, and offers plenty of food (sorry) for thought about parental loyalty and moral compromise.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro had been sitting reproachfully on my shelves for far too long. I finally read it over a few August days. While I still think I prefer Never Let Me Go, this shorter novel is quietly devastating. Stevens’ unwavering devotion to professional dignity becomes, by degrees, a tragedy of emotional repression, and the book left me reflecting on the cost of leaving important things unsaid until it is too late.

Brat, the debut novel by British novelist Gabriel Smith, comes from a younger and brasher literary generation than much of what I usually read. Like novels by Eliza Clark, which I have enjoyed in recent years, it has a sharp, whip‑crack energy. The narrator is gloriously unreliable, and there were moments when I feared the story might tip over into zany excess. Instead, it consistently skates along the edge of my tolerance and then pulls back, like a rollercoaster that knows exactly when to brake. It is also, at points, laugh‑out‑loud funny.

I completed Martin Amis’s so‑called “London Trilogy” in 2025 by finally reading The Information, a novel I first bought – and abandoned – nearly thirty years ago. As I noted last year, Amis’s prose struck me as impenetrable in my late teens and twenties, but has become increasingly hilarious and beguiling as I approach fifty. I did not enjoy this quite as much as London Fields or the riotous Money, but it still delivered plenty of caustic pleasure.

To close out the fiction section, I once again found myself drawn to dystopian satire. Mania by Lionel Shriver amused me by imagining a society in which discrimination based on intelligence is taboo, leading to the abolition of exams and the idea that anyone should be free to practise medicine. The consequences are, predictably, disastrous. I also read Ray Bradbury’s classic 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, depicting a world in which books are outlawed and burned. Reading it in 2025 felt depressingly less hypothetical than I would like.

Non-Fiction

My consumption of finance and investing books has slowed in recent years, but one that stood out in 2025 was Money: A Story of Humanity by Irish economist David McWilliams. It traces the incremental development of financial systems over thousands of years, and the profound ways they have shaped human lives. It manages to be erudite, irreverent and genuinely enlightening, no small feat for a book about money.

The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness by Jonathan Haidt is a book I wish I had read sooner. It has materially influenced how I think about parenting. Haidt’s core arguments – that social media is damaging to children’s mental health, and that over‑protectiveness in the physical world does real harm – are persuasively and soberly made.

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors That Determine the Fate of Every Project from Home Renovations to Space Exploration and Everything In Between by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner has an unwieldy title but a compelling thesis. Drawing on case studies from across industries, including enterprise software, it explores why large projects so often fail, and what distinguishes the rare successes. I found much here that resonated with my own professional experience.

The political dimension of getting things done is tackled in On Leadership: Lessons for the 21st Century by former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. I found this unexpectedly fascinating, and in places surprisingly practical.

I have long had a fondness for remote places and the idea of temporarily getting away from it all, particularly in Scotland. In that vein, I enjoyed Bothy: In Search of Simple Shelter by Kat Hill, which celebrates the pleasures of seeking refuge in these basic, often isolated buildings in the Highlands. Both the subject matter and the writing reminded me of The Outrun by Amy Liptrot, which I read a couple of years ago.

Source Code: My Beginnings by Bill Gates is the first volume of the Microsoft founder’s autobiography, ending in the late 1970s after the company’s first deal with Apple. As I have mentioned in previous years, I now take far more pleasure from autobiographies than I once did, and I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Gates’ account of his formative years. His life hack of owning two copies of every school textbook – one for home, one for school – to avoid carrying them around while projecting nonchalance was particularly delightful.

It wouldn’t be 2025 without at least a couple of AI‑related books in the list. Algorithms Are Not Enough: Creating General Artificial Intelligence by Herbert L. Roitblat was recommended by Richard Campbell during his talk at NDC Porto last year. It is a patient, thoughtful exploration of the gap between well‑structured computational problems and the ill‑structured insight problems humans solve with ease. We may not be heading for an AI apocalypse just yet.

I also enjoyed Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI by Yuval Noah Harari. As with his earlier works, it sweeps across vast stretches of human history and speculates on how long‑running patterns might continue into our technological future.

As ever, I read several books about music this year, including two excellent studies of The Beatles. With a Little Help from Their Friends by Stuart Maconie tells the band’s story through the lives of a hundred people who influenced or intersected with them – a simple idea that works beautifully. John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs by Ian Leslie is a deeply researched and surprisingly fresh take on a story that has been told countless times before.

I also greatly enjoyed Afternoons With the Blinds Drawn, the second volume of memoirs by Suede frontman Brett Anderson, following Coal Black Mornings. Covering the period of the band’s major album releases, it prompted me to listen to their back catalogue again with renewed attention. Anderson writes with honesty and clarity, without a trace of pretence.

Finally, the book that made me laugh the most this year was Thatcher Stole My Trousers, the second instalment of Alexei Sayle’s memoirs. Covering his journey from art school to television fame, it contains set‑pieces I doubt I will ever forget. His account of meeting Walid Jumblatt in a London cinema and asking his opinion of Rocky will live long in my memory. I listened to this on audiobook while driving around Germany on our summer holiday. My eighteen‑year‑old son affected an air of total indifference behind his AirPods, but kept involuntarily chuckling too.

Looking ahead to 2026, I suspect my reading habits will settle into something like a 50/50 split between fiction and non-fiction. I’m keen to get back into listening to Audible while walking the dog, a habit that has quietly slipped but which always felt like time well stolen back. Having proved to myself that I can still happily lose weeks inside a genuinely big novel, I want to lean further into proper literature, rather than circling it nervously from a distance. And, somewhere amongst the family sagas, dystopias and memoirs, I should probably read something unapologetically technical again, if only to reassure myself that my architectural instincts haven’t quietly atrophied. There is no great plan here, just the reassuring sense that I may choose — and that, at this stage of life, feels like indulgence enough.